The Impact of China's Ban on Gallium, Germanium, and Antimony on Semiconductor Companies

The trade war between the United States and China has been ramping up, with only a few weeks left until 2025. In a surprising move, the Biden Administration commenced a third crackdown on Chinese chip ambitions with a new set of restrictions that added 140 companies to its Entity List. This list requires companies to petition for licenses to ship to firms on it, which are usually denied.

In response to the new restriction package, Beijing banned exports of gallium, germanium, antimony, and other key materials used in advanced semiconductor manufacturing. Last year, gallium and germanium faced a partial ban in response to U.S. restrictions. Businesses planning to export either material were required to obtain licenses and identify the companies or countries in the region to which it would be imported or where the end users were located.

In August 2024, China enacted another partial ban on antimony materials in response to U.S. restrictions on components used for artificial intelligence (AI). This latest action, however, is markedly different from the previous controls as this was a complete ban on exports of gallium, germanium, antimony, and other materials to the U.S., effective immediately. No licenses. It is a total ban that targeted the United States.

As of today, there is still no word on how this recent ruling by Beijing will be enforced. However, translations of the notice detail that the export ban is to prohibit the use of these items within military applications and that stricter end-user and end-use checks will be implemented on exports to ensure compliance.

This move has caused massive ripples through the global semiconductor supply chain, as these minerals are critical to producing many advanced electronic components. The ban could increase prices, lead to longer lead times, and cause shortages.

The Semiconductor Industry and the Minerals

Over the last few years, gallium and germanium have become more widely used to produce advanced semiconductors, high-performance electronic devices, optical fibers, and more. Gallium is critical in producing gallium nitride (GaN) semiconductors, which have been shown to outperform conventional silicon semiconductors due to their reduced size, weight, and cost, as well as their increased energy efficiency and thermal management.

While initially used in military applications, GaN components have proliferated in many markets in recent years thanks to their voltage handling, durability, and switching speed capabilities. The boom in AI has led to an extraordinary demand for power and data centers where GaN components can be used. These components are also key in achieving sustainability goals, as their efficiency contributes to fewer emissions, leading to end-use emissions falling nearly 30% compared to traditional silicon.

Similarly, germanium is another popular choice over silicon thanks to its charge carrier concentration, electron mobility, and efficiency in photonic devices. Germanium is most often used in fiber-optic systems, infrared optics, and specific types of transistors.

Meanwhile, antimony, which joined the banned minerals list this year, will likely have the most considerable impact due to its use in numerous advanced semiconductors and other electronic products. While not exceedingly common, it is used to manufacture different types of batteries, semiconductors, and diodes. The aerospace and defense industry, the primary market targeted by these recent bans, heavily relies on antimony for numerous applications.

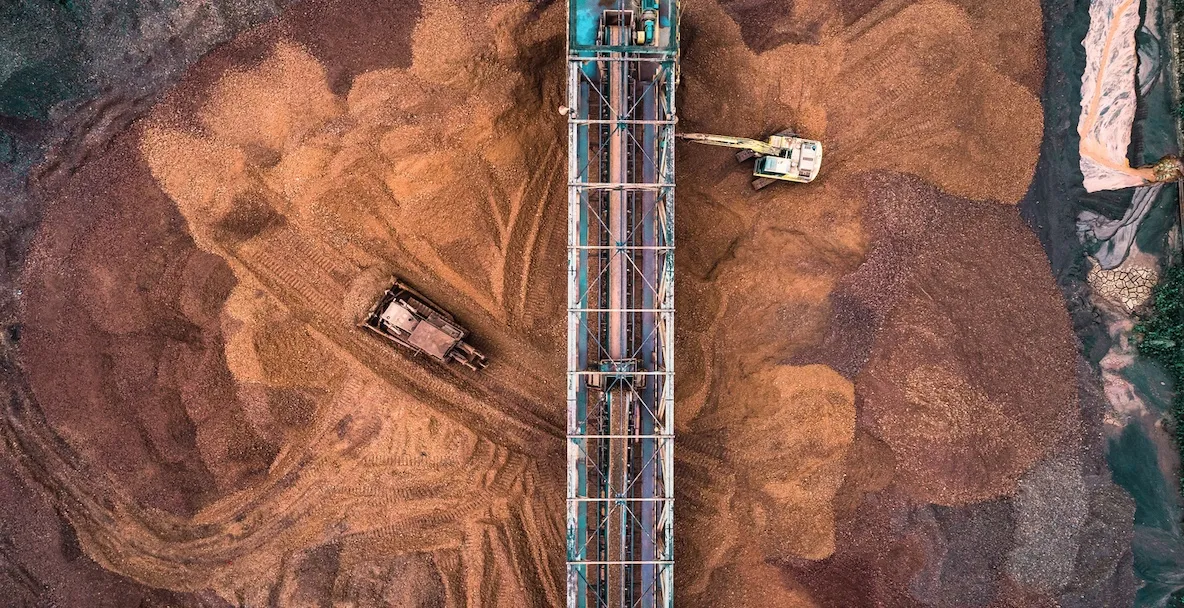

China is the dominant global producer of all these materials. It is the largest producer of gallium and germanium, at 90% and 60%, respectively. The U.S. alone imports almost 95% of gallium and 80% of germanium from China. Regarding antimony, China still makes up a large portion of the global market share, at 48%, with Russia coming in first as the leading producer of gold-antimony. Like gallium and germanium, the U.S. imports 85% of its antimony supplies as the country stopped mining for antimony domestically in 2001.

Given the substantial reserves and its place as a leader in the global production of these raw materials, China’s ban could have a far-reaching impact on the semiconductor supply chain. The semiconductor supply chain has been exceedingly vulnerable over the last few years due to the ongoing trade war, severe weather, and the COVID-19 pandemic. The industry’s dependence on these critical minerals makes it vulnerable to disruptions like this.

The Impact

With the lion’s share of the global production of gallium, germanium, and antimony, this export ban has triggered supply chain issues. While many companies and countries have reserves of these raw materials, the length of the ban will reflect the difficulty it takes organizations to secure the necessary quantities. Should the ban last for months and supplies drain up, this could eventually result in production delays and manufacturing slowdowns for key semiconductor products such as sensors, LEDs, memory, and optoelectronics.

Aside from China, Russia and Tajikistan account for 30% of the globe’s mined antimony, leaving the U.S. and some of its allies with few options. As American companies identify other sources, it may take time to establish a secure supply line, leading to long lead times.

When gallium and germanium were first banned, industry experts like Tim Worstall said minerals could be found elsewhere if a total ban was implemented.

“Given the size of the planet and the reality all of it is made from the same 90 elements, it’s difficult for there to be such an absolute shortage,” said Worstall in the article Don’t Worry About China’s Gallium and Germanium Export Bans. “There can be – and is in this case – a shortage of plants that extract and refine, but not of the base material. So, the solution is a couple more plants to extract and refine gallium and germanium.”

Others weren’t so upbeat.

Markus Roas, a metals business manager at Indium Corporation, said that U.S. companies were finding it challenging to get licenses and only had weeks' worth of germanium and gallium left. Roas went on to state that they only had a week’s worth of germanium and gallium remaining, and that was in September before the total ban was instated. Until this point, the exports of gallium and germanium were a fraction of what they once were.

This doesn’t even address the cost. Since the partial ban on antimony in August, the price of antimony trioxide has more than doubled to over $39k per metric ton.

“It’s a sign of the times. The military uses of Sb (antimony) are now the tail that wags the dog. Everyone needs it for armaments, so it is better to hang onto it than sell it. This will put a real squeeze on the U.S. and European militaries,” Christopher Ecclestone, a principal and mining strategist at Hallgarten & Company in London, told CNN shortly after Beijing announced the curbs on antimony exports.

"It is no secret that antimony prices worldwide continue to hit fresh record highs after a prolonged period of supply constraints," said United States Antimony Chairman Gary Evans. "The upswing in prices has gathered pace which is underpinned by depleting domestic antimony resources in China as well as other parts of the world."

Only one mine in the U.S., Perpetua’s Stibnite gold-antimony mine project in Idaho, could provide a domestic supply. However, it would only produce enough antimony to supply roughly one-third of America’s industry needs.

Orders will quickly exceed supply without sufficient reserves to meet global demand in the short term, contributing to shortages and rising costs.

The price hikes could, in turn, increase the cost of end products like smartphones, computers, and automotive electronics, thereby straining both businesses and consumers. Companies that rely on tight margins may struggle to absorb these additional costs, potentially leading to higher consumer prices or reduced manufacturer profit margins. Capital spending has already been tight for manufacturers since the dramatic downturn in 2023 and the lingering excess combined with flat demand through 2024.

With this strained capital, companies might be unable to invest in research and development of new semiconductor materials or other supply sources. Substituting new materials in existing technologies can be complicated. Gallium, for instance, is valued for its high efficiency in specific applications, and no single material can easily replicate its performance.

However, China’s bans on critical minerals have pushed the U.S. and others to look for raw materials elsewhere. The U.S. government has already planned to fund the gold-antimony mine project in Idaho. Similarly, there has been a push by global governments and lobbyists to source materials outside of conflict areas to meet ethical and financial obligations.

While this is a good solution, it will still take time to achieve, adding complexity and challenges to an already taxed global supply chain. In the meantime, countries will likely seek to secure access to critical raw materials by entering into trade agreements or forming partnerships with other major producers, which can reshape the global semiconductor landscape.

The ban also presents a unique opportunity for innovation in the semiconductor industry. Faced with potential material shortages, companies may accelerate research into alternative technologies that could reduce their reliance on these rare elements. This could spur breakthroughs in material science and manufacturing processes and develop new semiconductor architectures more resilient to supply chain disruptions.

Likewise, there is growing interest in two-dimensional materials, which could eventually reduce the industry's dependence on traditional materials like silicon, gallium, and germanium.

A Changing Landscape for Semiconductor Companies

China’s export ban on gallium, germanium, and antimony marks a significant turning point for the global semiconductor industry. The immediate effects of supply chain disruptions and rising material costs will pressure companies to adapt quickly. However, increasing raw material costs and longer lead times will still impact many organizations. If the ban persists, it could accelerate efforts to diversify supply sources, invest in alternative technologies, and strengthen domestic production capacities in regions outside of China.

The ban will challenge many semiconductor manufacturers in the coming months. After two years of flat consumer demand, exacerbated by the global semiconductor shortage, many companies struggle to stay afloat in a rapidly shifting landscape. Access to critical raw materials like gallium, germanium, and antimony is becoming increasingly important due to the heightened demand for electronics due to AI and electrification efforts. Thus, industry players must secure their supply chains and invest in sustainable solutions for the future.

As a global electronic component distributor, Sourceability works alongside franchised partners sourcing experts and invests in new digital solutions to provide unparalleled supply chain solutions to its clients. The coming year promises to bring new challenges for the semiconductor supply chain, with raw material bans, new tariffs, and the ongoing trade war being just a few of these problems.

Luckily, Sourceability collaborates with its experts to develop innovative ways of overcoming even the worst supply chain disruptions.